Refugee Art

Art has always been a mystery to me. And before our cycling journey, I was unable to fully grasp the importance of visually expressing oneself. But during the Refugee Roads journey, this changed.

After our hasty arrival in La Liniere Camp in France, which was the first refugee camp I have ever been to, I took a walk around the wooden cabins to get to know the facility and to sort out my thoughts. At the back of one of the huts I stumbled upon this art piece:

It seemed so unreal. There I was, in eyesight of the train tracks heading to the UK, looking at this painting of a bridge at night that wished everyone that was about to attempt the dangerous crossing simply “Good luck”. Trying to grasp this paradox moved me deeply and I teared up.

From there on out we saw works of art at almost every stop we made. Ranging from simple slogans sprayed on camp walls to comprehensive and professional painting projects, art seemed to be one of many underlying themes of the refugee crisis in the Balkans.

But why? How do the concepts of ‘art’ and ‘refugee’ fit together? Well, there are three points that I took away from our encounters that each may just deliver a part of the answer.

First of all, I came to learn that the desire to take past experiences, emotions and creative thoughts is inherently human and does not know any borders. Art pieces act as a universal language, thereby transcending existing cultural, social, and language boundaries. Through creating, the artists can reach fellow humans on a communicative level which would otherwise be unavailable to them.

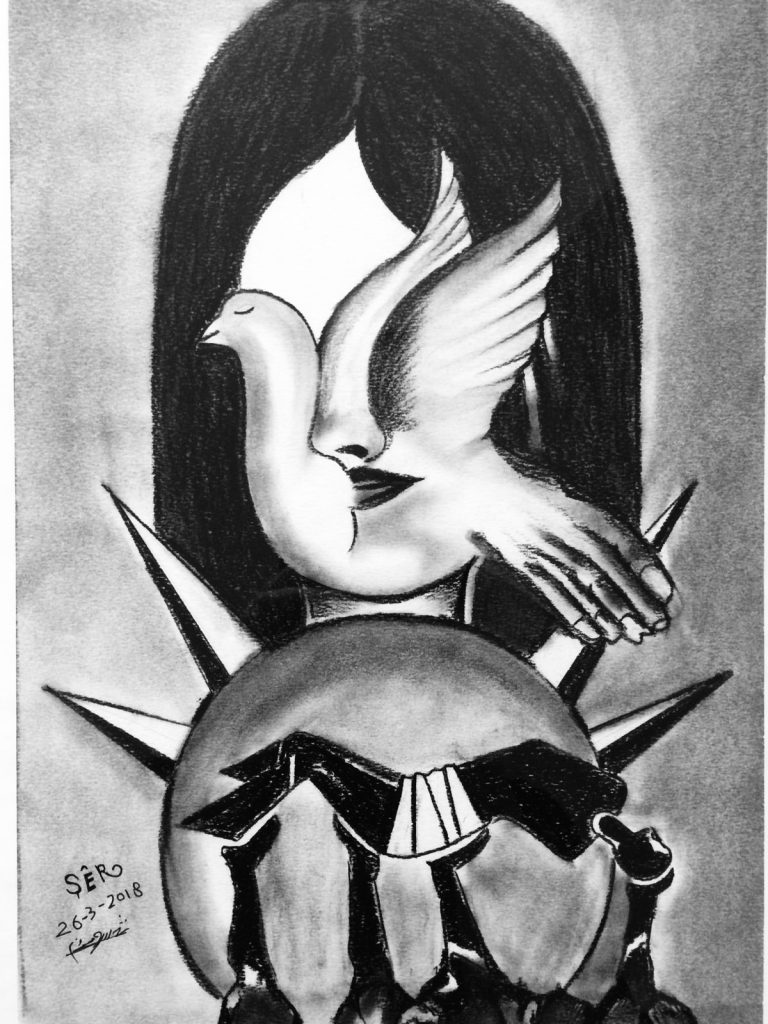

Artwork Credits: Ghazwan Assaf

Secondly, we found that especially in such dire living situations, creating drawings or paintings may have a therapeutic effect. Shergo, who we met in a refugee camp in Northern Macedonia created over 200 pencil drawings throughout his four-year journey. He told us that he uses his drawings as an outlet to transfer the experiences of his journey out of his head and onto the paper. “My art helps me to keep a clear heart”, he said.

And thirdly, refugee art functions as a means of creating empathy for the situation of the ‘Other’. Through participatory art projects in refugee camps, refugee art shows in western museums, just as much as with public art installations around the world, conversations around migration are created. When the message behind a drawing is being received by a person in the host society, a small bridge of understanding is developed, thereby facilitating integration in the long run.

These bridges are being built not only from people who are currently fleeing their homes but also from former refugees who have arrived at their destination. Through organizing galleries centered on the topic of migration, publishing art online, and giving media interviews about their work, their art helps in raising public awareness.

The most famous example of this is the renowned artist Ai WeiWei. Growing up as a refugee himself, he centers a lot of his pieces on the topic of migration to showcase the ‘narrow-minded’ attempts used to ‘create some kind of hatred between people’. He also produced the feature ‘Human Flow’ to inform his viewers of the global refugee crisis.

More Info:

The Syrian Refugee Art Initiative

Janso Isso’s Story – A Kurdish Artist in Canada

Ai Weiwei’s Art Pieces about Refugees

“The refugee crisis is not about refugees. It is about us.” – Ai Weiwei